Mark Cocker

'It takes a whole universe to make the one small black bird'

Beetles of the World: Unofficial Bookclub No 10

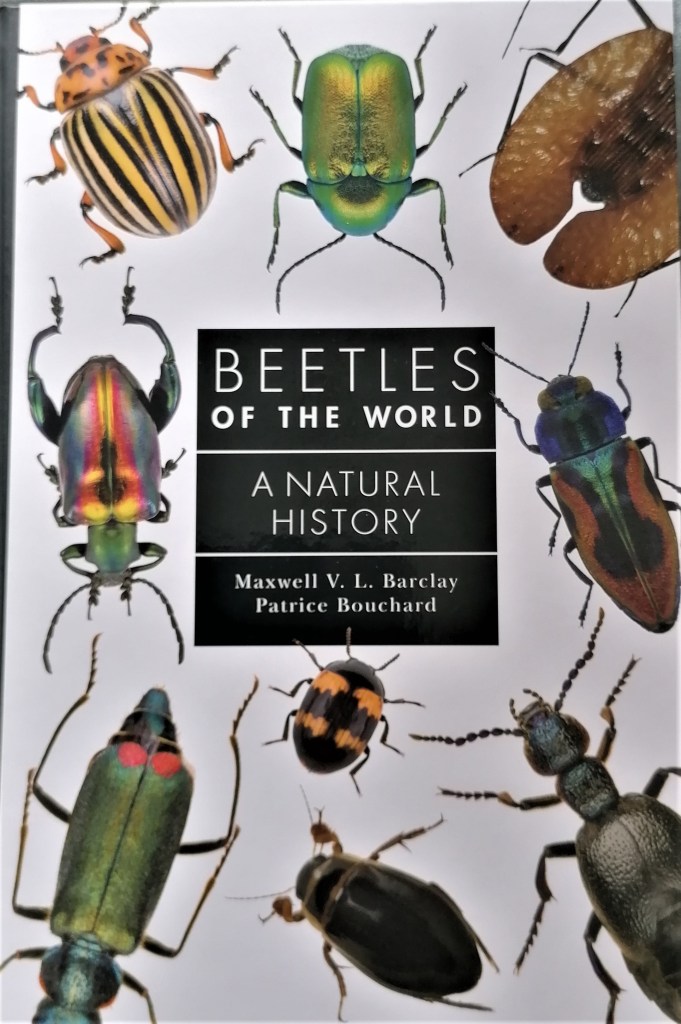

Beetles of the World: A Natural History, Maxwell V L Barclay & Patrice Bouchard, Princeton, hbk £25

It’s time to think of beetles as something other than a tiny black creature scuttling insignificantly through the vegetation. As Alfred Russell Wallace pointed out of the general public, ‘Tell them … they are ignorant of one of the most important groups of insects inhabiting the earth, and they think you are joking’. But no. Beetles are among the superpowers of terrestrial life. If humans vanished, there’d be barely a ripple in the biosphere’s functioning processes, except of course a massive, immediate upsurge in the abundance of almost everything else. Remove beetles from life and there would be major evolutionary ructions for hundreds of thousands, if not millions of years.

There is a lovely anecdote in this new book that trades on this near-incredible dominance of beetles. A famous biologist JBS Haldane was once approached by a group of Christians and asked whether his career had given him any insight into the mind of their deity. Back instantly came his response: She or He had ‘an inordinate fondness for beetles’. There are apparently 400,000 beetle species now named, representing by a massive margin the biggest order in the class Insecta. It equates to nearly a quarter of all life forms so far identified and they operate in a multitude of ways. They predate everything from whole trees to other beetles. They, in turn, are food for almost all life forms including bacteria and lions. They are pollinators deluxe for huge numbers of plants. Above all, they’re among the planet’s principal undertakers and refusal-disposal agents.

Now they star in this beautifully illustrated work from Princeton. The volume, in turn, forms part of the publisher’s charm offensive on behalf of the most overlooked, under-rated and downright despised of all animals – Insects! The entire series is evolving into a thing of beauty (not forgetting recent further titles on snakes, seaweeds and turtles). Yet at somewhere between £25 and £30 each, the question should be asked…. are they worth it?

I’m an author and biased, but to put the price in context, I recently heard of someone who bought a round of drinks at a London pub – two large glasses of wine and two pints of beer. For the price they paid for these four drinks (£112) you can get not just this beetle book, but the ants, the bees (see my review of that volume here) and a fabulous new survey called The Complete Insect: Anatomy, Physiology, Evolution and Ecology by David Grimaldi. The books will last you a whole lifetime: I rest my case.

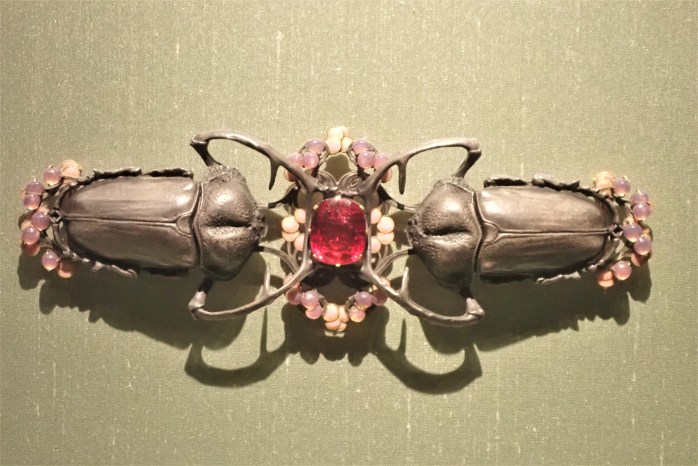

One takeaway highlighted by Barclay and Bouchard – aside the fact that beetles are eaten in many an Asian marketplace – is how beautiful the beasts can be. Look at this Filipino flower chafer above. There are 300 such images in their book. I’m not surprised that humans have been captivated by their extraordinary architectural structures as well as the shiny metallic colours of beetles. Look at these glorious stag beetles in a Lalique piece from the beginning of the twentieth century.

The book includes a section on this cultural importance to beetles – as inspiration for art and literature, but also as a source of ideas embedded in the religious beliefs of ancient Egyptians. Their god Khepri was evoked through images of scarab or dung beetles. The sight of these ubiquitous animals rolling their balls of dung across the ground was seen as symbol for the chief deity Ra, progressing the sun across the heavens. Somehow the ancient Egyptians intuited that there was some fundamental connection between the beetles’ reproductive habits, the passage of our daily star and the totality of life. And how right they were!

I want to add a further observation about the beauty created by beetles and also about their centrality to life.

Recently I found this series of patterned excavations inscribed on the surface of a dead tree by a member in the bark beetle family the Scolytidae. This species is a vector of so-called Dutch elm disease, which has removed most of the mature elms from the British landscape, decimating many millions of trees in the process.

The story involves a pathogenic fungus rather wonderfully named Ophiostoma (the snake-mouthed). It works in harmony with the bark beetle to spread fungus spores tree to tree. In return, the fungus detoxifies the elm’s defensive chemicals, it helps to break down tree tissue and prepare it as food fit for a small beetle. In addition, the two predators – beetle and fungus – create an effect that turns the elm upon itself. The fungus somehow encourages the tree to produce chemical signals that are attractive to yet more bark beetles. Elms are thus recruiting the agents of their own demise. It may not be beautiful in any conventional sense, but this much-lamented process entails its own kind of exquisite complexity. It also shows how we think of the British countryside as somehow belonging to us, and that is ours to do with as we wish. When it comes to wholesale landscape changes, however, beetles are easily as capable. Beetles are beautiful and brilliant and powerful. This superb book shows us exactly how.