Mark Cocker

'It takes a whole universe to make the one small black bird'

Shieldbugs & Ponds, Pools and Puddles: UNOFFICIAL BOOKCLUB NO 12

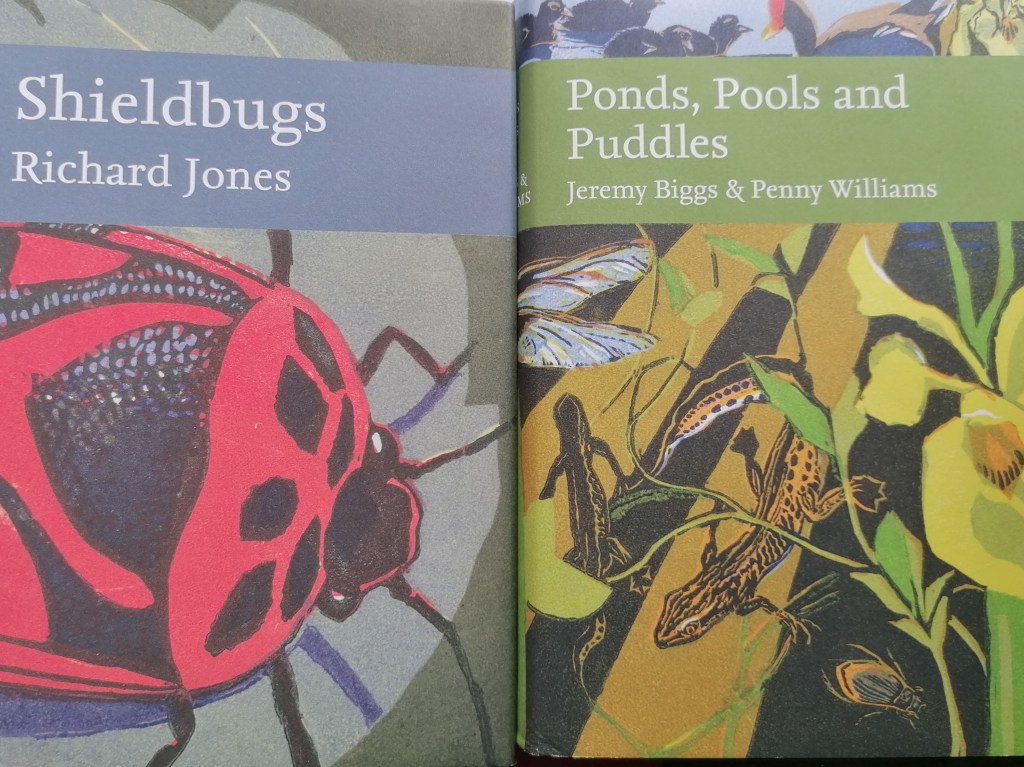

Shieldbugs by Richard Jones, New Naturalist 147, Collins, £65, pbk £35

Ponds, Pools and Puddles Jeremy Biggs and Penny Williams, New Naturalist 148,, Collins, £65, pbk £35.

This is a long overdue piece on the last two in the New Naturalist series, which is, of course, not at all new. The full library dates back 80 years to a first title Butterflies by E B Ford in 1945. The postwar period was marked by a profound national upwelling of attention for the nonhuman world and the series was intended to capture and reinforce our new-found passions for nature. It’s hard for such a venerable list to sustain relevance and cutting-edge approaches but, if anything, the New Nats series has undergone a renaissance recently in quality and subject matter. Trees by Peter Thomas has the makings of a classic. And these two new titles match that high benchmark.

One thing that is striking is the trouble taken by the authors. It is particularly true of Ponds, Pools and Puddles, given that the volume was conceived even down to its title in the 1940s by the late Alistair Hardy. Biggs and Williams have picked up that baton thrown down long ago, but have taken a further 15 years to produce the book. That prolonged gestation is reflected in its exhaustive treatment of the theme – a whopping 611 pages – but the authors has also gained a huge advantage. There has been a revolution in understanding of, and depth of attention, for ponds, pools and puddles. The authors have captured all this new material. It means their book will be an important standard and key resource for a very long time.

At 450 pages, Shieldbugs by Richard Jones provides equally comprehensive coverage. I doubt the layperson would want material on this relatively small insect group that isn’t included here. Shieldbugs are in the order Hemiptera and comprise a cluster of families known as the Pentatomomorpha, of which there are nearly 18,000 species named worldwide and 190 in the UK. What is striking about them is their beauty. Their wings are protected underneath a harder sheath of chitin called a scutellum. These ‘shields’ are often astonishingly bright and colour-coordinated and the book is packed with beautiful images as Jones outlines his species-by species accounts and unpacks their identification.

The author’s own daughter, Verity Ure-Jones is also a talented artist and has done a wonderful job of capturing precisely the details of these remarkable insects. But more broadly one can see that the insects themselves are an artist’s dream and I briefly mention a beautiful book Heteroptera: The Beautiful and the Other, Scalo, 1998, by Swiss artist Cornelia Hesse-Honneger that Jones seems not to have known, despite his exhaustive trawl of the cultural resonances inspired by shieldbugs and despite CHH exhibiting at the brilliant Groundwork Gallery in Kings Lynn in 2020. Heteroptera excels in capturing shieldbug aesthetics.

While these little beasts possess what look like the elytra of beetles (the domed cases enclosing and protecting their wings), they are a very different type of insect. Beetles, like moths, or bees and wasps, proceed to adulthood via the total transformation known as metamorphosis. Shieldbugs do things differently, developing through a sequence of related stages or instars. The eggs turn into a little bug – technically a nymph – that progresses and shed its skin intermittently to acquire full adult condition. It is known as hemimetaboly and Jones gives a clear synoptic overview of the life-path for hemimetabolous insects and the underpinning biochemistry. He has a total grasp of the science while deploying prose that is fluent, engaging and precise. Here’s a small sample:

“When it is ready to hatch, the shieldbug embryo .. starts to swallow air and uses its inflating gut as a tough taut internal bladder against which it can increase the pressure of its haemolymph [insect blood]. Using rhythmic muscular movements it starts to expand its body, pushing the hard egg-burster up against the top of the eggshell. The shell bursts .. and the lid flips open. Empty eggshells usually have the hinged lids still attached and look like a stack of empty tin cans.”

The author is an arch proselytiser for his shieldbug religion and never misses opportunities to stray off-piste to capture amusing stories. I particularly love his account of the shieldbug pioneer George Kirkaldy. These details form part of Jones’ wider and superb historical account of all shieldbug research. But Kirkaldy (above: note how his moustache bespeaks mischief and salacity!) described a suite of new genera, which he named with the suffix -chisme. The word derives from the Greek for shieldbug Cimex. Undetected by his straightlaced entomological colleagues, cheeky old George honoured a suite of female friends with new shieldbug names such as Peggichisme, Florichisme. The pronunciation of these ends up as ‘Peggy-kiss-me’ and ‘Flori-kiss-me’. One assumes that Jones delights in this sort of thing partly to soften his subject and give it what we might call … ‘sex appeal’. It works brilliantly.

But on the issue of names I have to take to task, not so much Richard Jones, but the editors of the New Naturalists. This volume follows a pattern used in the series to cite English names for an animal or plant etc, on first mention and thereafter to use only scientific nomenclature. So, for example, the green shieldbug after a first encounter, becomes ever after Palomena prasina. Actually that is one of the slightly more memorable constructions: try to get your head round Gonocerus acuteangulatus (English name: box bug), or to take another group of insects, Pseudomogoplistes vicentae (the mole cricket).

The real problems arise when in a later chapter – say 30 pages after that first helpful inclusion of the English and Latin equivalents – you re-encounter the organism but only in its latinate form. You can’t remember who that name refers to and so you have to look it up in the index. By the time you’ve done that, you have lost the flow of the account and then you might have to repeat the same procedure – because the author refers to four other species only by scientific names – time after time after time. You could take the trouble to write them all out in your own private list, or you could annotate your own copy of the book every time you come across unfamiliar scientific nomenclature. But then why didn’t the authors and editors take on this task on your behalf? Why didn’t they implicitly set out to include you and me as readers of the book?

Names matter. They go to the heart of the whole naturalists’ project. And they go to the heart of the New Naturalists series. Who are the books for and what roles should they play? These are important matters and I think the Collins and New Naturalist editors are failing readers, but much more important, failing nature itself.

We are in the midst of the Sixth Extinction. One way of reversing the catastrophic loss of nature is to create stories that the public can understand and which help people to recognise the importance of the nonhuman living world. Richard Jones loves shieldbugs. He wants us also to love and care for them. He gives us stories that make them relevant. In fact, why else would you deploy a hugely accessible, humour-laced, easy-to-read style full of fascinating anecdote if that were not the purpose? Yet, when it comes to the name, the singlemost important and foundational part of the story-creating process, you have shut me out. And you are shutting out all those who, like me, love shieldbugs, but also love grasshoppers, dragonflies, butterflies, moths, bees, birds, mammals, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, plants, mosses and fungi. Like many others I conduct all my studies of these in English names.

Let’s clear away one matter. Scientific nomenclature is important and essential. I am not suggesting that it can only be with English names. In the case of Jeremy Biggs and Penny Williams’ glorious volume on ponds there are no common names for many of the aquatic organisms they are talking about. In fact, they break with the New Naturalist traditional format and seem to use a sensible and pragmatic mix of standard English wherever they can – frogs, newts, toads etc – with scientific nomneclature where there is no alternative.

One possible solution is for the editors at the New Nats to request common and scientific names in tandem. But what is particularly sad and important is that the New Naturalist series has now included major volumes on grasshoppers, solitary bees and bumblebees. Of grasshoppers we have just over 40 species in Britain. Of bumblebees there are fewer than 25. All of them have long-established, stable, widely used, and easy-to-remember common English names, but the authors of those volumes have insisted on using primarily confusing, difficult-to-remember scientific names such as Pseudomogoplistes vicentae.

To return finally to those wonderful shieldbugs: you tell me which is easier to acquire? which name allows you to start to create and understand stories about these fabulous organisms? A name like Gonocerus acuteangulatus or box bug? I rest my case.

Pingback: Books really do furnish a Christmas – Mark Cocker