Mark Cocker

'It takes a whole universe to make the one small black bird'

Christmas Books 2025

We’re constantly being told about the new-tech that will change our world. No technology has been more transformative across the whole of my life than the one developed in 1455: the good old printed book. I’ve read something like 47 in 2025 and in case you’re needing a few pointers for Nature-oriented friends at Christmas or spending wisely the all-important gift voucher in the New Year, here are a few of my suggestions:

I’m very been slow to read 2018 Pullitzer Prize winning novel by Richard Powers The Overstory 625pp, Vintage. While I wouldn’t list it as my favourite book of 2025, it is as massively accomplished, inventive and thought-provoking as the reviewers said. It describes the interweaving lives of several tree-campaigning Americans across 30 years’ of activism to save pristine old-growth forests. It is as uplifting for its rich detail on tree biology and their essentially sharing lifeways, as it is bleak on capitalism’s relentless conversion of life into product. Nihilism with a Green Man’s heart.

(Incidentally, my novel of the year was Haydn Middleton’s The Ballad of Syd & Morgan, Propolis Books, £11, 165 pp, which describes a fictional meeting of E M Forster and founder-member of Pink Floyd Syd Barrett. In the Spectator I wrote: “Full of tender humour and subtle psychological insights, Middleton’s novel manages to be utterly convincing on the most unlikely of chance encounters.”)

The tree theme has been to the fore this year and another I received in April 2025 was this superb field guide, Trees of Britain and Ireland, by Jon Stokes, (Princeton 360pp £15). Trees are notoriously difficult and complex – there are, for example, 42 recognised microspecies of whitebeam – but Jon goes to town on everything. And he does so in ways that finally allow people like myself to separate goat willow from grey willow, English elm from wych elm. Like so many of the Wild Guides collaborations with Princeton, this books sets new standards for what a field guide should and can cover.

Sophie Pinkham’s The Oak and Larch: A Forest History of Russia and its Empires (William Collins Jan 2026, £25) isn’t quite out. This new book by an American cultural historian looks really great. It also does several important things. It reminds us that Russia is more than just psychopathic tyrants and corrupt billionaires. It holds more trees than there are stars in our galaxy; it is home to some amazing indigenous peoples, such as the Khanty, who believe in silence as a gesture of respect to the forest and its inhabitants, who had no concept of Nature or wilderness and who recognised no division between the forest and home. These are my kind of people, my sort of place. Pinkham’s book promises to be important. I am reviewing it shortly.

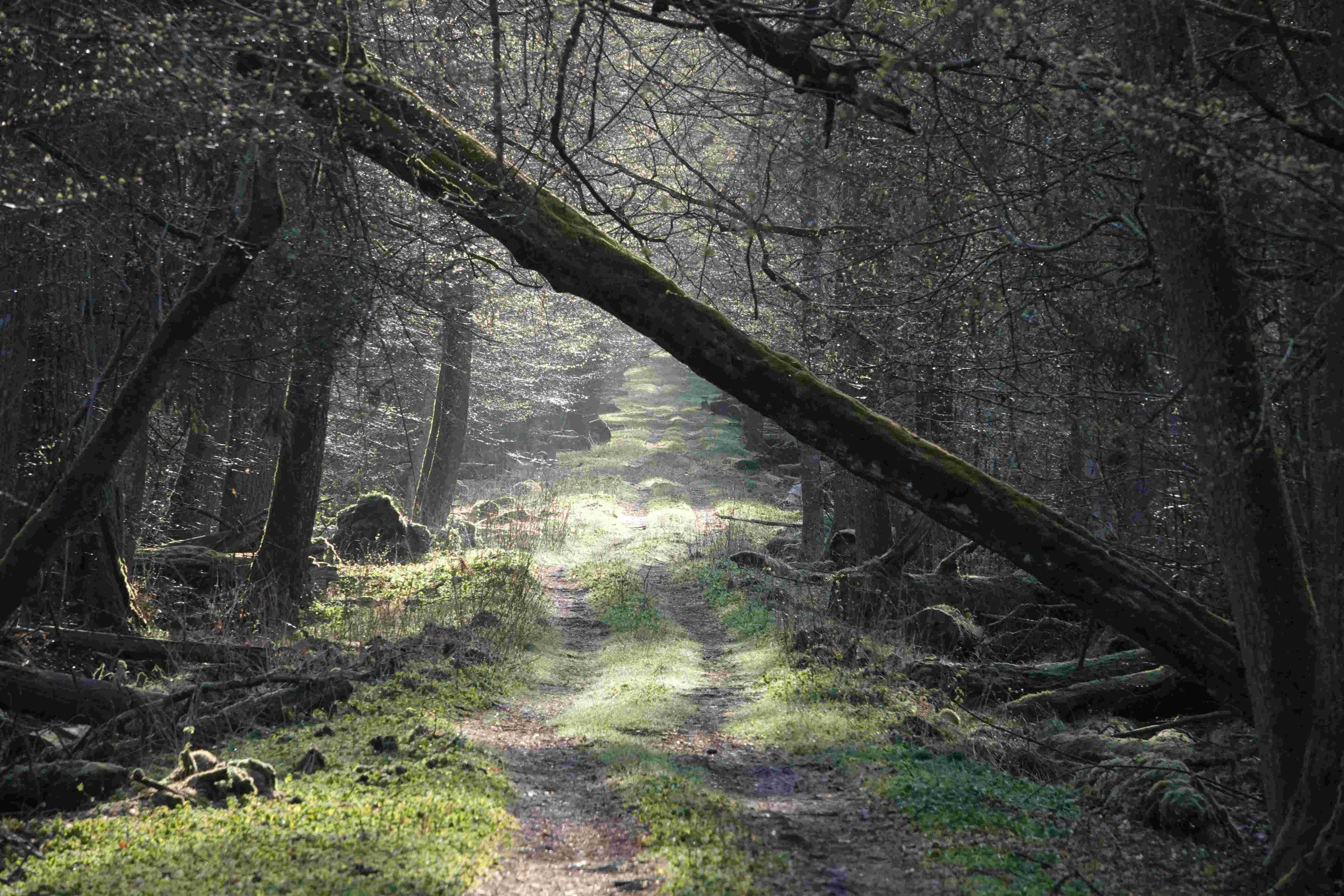

Finally did you know that Boris Yeltsin with the leaders of Ukraine and Belorussia signed the dissolution of the USSR in Belovezha? This is the Belorus side of the greatest forest in Europe known as Bialowieza, in Poland. I saw it briefly in April. My wildlife encounter of the year: so, here’s an image interlude on this extraordinary place. The main takeaway for Britons from Bialowieza, is our unwillingness to acknowledge that, in woods, death and life are one. Dead wood is new life. More life. Tidiness, by contrast, is lifelessness.

The tree theme continues because all those books sent me back to Peter Thomas’s Trees, HarperCollins, 512pp, 2022,

It is quite simply the best New Naturalist I’ve ever read. You can pick it up secondhand as a bargain for c£20. It is indispensible for anyone who cares deeply about Nature, woods and life. In a way it is as mind-stretching as Powers’ The Overstory

Paul Redshaw has self-published this lovely object: The Dales Slipper: Past – Present: A Revealing Investigative Account, pbk, 270pp, £19.99 It is a meticulous trawl and exploration of arguably the most charismatic flowering plant in Britain, the lady’s slipper orchid. The creature is known from just a handful of sites in northern England. I am hoping to go with Paul in 2026 to fulfil a lifetime’s ambition. You can buy the book or speak to Paul thedalesslipper@gmail.com.

Paul’s superb book led me back to Peter Marren’s glorious Rare Plants, British Wildlife, 2024, 396pp, £28. Like all Peter’s book it is worth reading for his lifetime’s accumulation of expertise. In this instance it is doubly rich because he has had two goes at the same title. A rare feat indeed by a rare scholar of Nature.

One of my book highlights in 2025 was Carl Safina’s Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, Souvenir, 2016, £9.99. Grounded in extensive field observation as well as scrutiny of the latest scientific literature, Beyond Words dismantles the age-old presumptions that every invidual animal – wolf, orca, elepant or chimpanzee – is nothing more than a representative of a generic organism; worse, that each animal has no individual agency, no feeling, no cognitive capability above instinct and no deep-rooted connection to its fellows. Safina thoughtfully but firmly obliterates the old Cartesian myth that we are the only species with consciousness and emotions. It set me thinking, in the context of my own discovery of the year. In 2025 I investigated the mimicry performed by singing male common redstarts. So far I have identified the vocalisations of 60 other bird species in the songs of male common redstarts. Safina’s book unleashed a world of speculation about what is happening and why each bird would do this and how it does it?

Probably the closest I will ever get to the Arctic is reading this frozen-white-knuckle ride of a thriller by Harry Whitehead, Claret Press 267 pp, pbk £11.95. White Road is both a page-turning disaster drama and a moral re-examination of the climate crisis and our species’ relentless need for more hydrocarbons. The author attends to the hour-by-hour twists in his plot, yet spliced to a forensic exploration of the human heart. He gives us a love letter to the extraordinary ice world of the Arctic: both its fragile beauty and its remorseless terrors. Before everything, the book strikes me as a singular, beautifully integrated achievement.

Health warning: if hard truths are not your thing, go no further. Earth Capital: The Long History of Capitalism and Its Aftermath: Alessandro Stanziani, Polity, 360p, £25, is not an easy read, but it is, as Thomas Piketty writes, ‘a must read’. Stanziani follows a singularly troubling inquiry into the way capitalism has interacted and shaped both us and the biosphere. Most powerful of all are the book’s revelations about the way largely Western capitalist entities are strengthening their grip on planetary resources. What possible hope for justice and equity can we hold when ten multinational corporations possess more wealth than the poorest 180 countries on Earth?

Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper, Bloomsbury, £20, 350pp. In his most important book so far, the chair of Natural England demolishes the arguments, often advanced by the super-rich to defend their interests, that Nature is an expensive luxury and its despoilation are the inevitable consequences of wealth creation. Juniper marshals his evidence brilliantly and shows how social justice and living within the means of our planet are part of a single achievable political project.

Finally the brilliant Jay Griffiths explores and amplifies some of the ideas discussed in Safina’s Beyond Words. Griffith’s own How Animals Heal Us, Hamish Hamilton, £20, is superb on these themes and especially in making a case for living with animals. I am so delighted that Jay is coming here (to Derbyshire) to talk about her new book in the Buxton International Festival. i hope you will join us in leafy July.

A fine selection, Mark. I did find The Overstory particularly bleak.

LikeLike

thanks Mike yes quite tough and my own views were not quite in accord with the universal praise but I did enjoy it and loved some of the characters especially the arboreal ones!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I generally preferred the arboreal ones…

LikeLike