Mark Cocker

'It takes a whole universe to make the one small black bird'

Christmas Books 2025

We’re constantly being told about the new-tech that will change our world. No technology has been more transformative across the whole of my life than the one developed in 1455: the good old printed book. I’ve read something like 47 in 2025 and in case you’re needing a few pointers for Nature-oriented friends at Christmas or spending wisely the all-important gift voucher in the New Year, here are a few of my suggestions:

I’m very been slow to read 2018 Pullitzer Prize winning novel by Richard Powers The Overstory 625pp, Vintage. While I wouldn’t list it as my favourite book of 2025, it is as massively accomplished, inventive and thought-provoking as the reviewers said. It describes the interweaving lives of several tree-campaigning Americans across 30 years’ of activism to save pristine old-growth forests. It is as uplifting for its rich detail on tree biology and their essentially sharing lifeways, as it is bleak on capitalism’s relentless conversion of life into product. Nihilism with a Green Man’s heart.

(Incidentally, my novel of the year was Haydn Middleton’s The Ballad of Syd & Morgan, Propolis Books, £11, 165 pp, which describes a fictional meeting of E M Forster and founder-member of Pink Floyd Syd Barrett. In the Spectator I wrote: “Full of tender humour and subtle psychological insights, Middleton’s novel manages to be utterly convincing on the most unlikely of chance encounters.”)

The tree theme has been to the fore this year and another I received in April 2025 was this superb field guide, Trees of Britain and Ireland, by Jon Stokes, (Princeton 360pp £15). Trees are notoriously difficult and complex – there are, for example, 42 recognised microspecies of whitebeam – but Jon goes to town on everything. And he does so in ways that finally allow people like myself to separate goat willow from grey willow, English elm from wych elm. Like so many of the Wild Guides collaborations with Princeton, this books sets new standards for what a field guide should and can cover.

Sophie Pinkham’s The Oak and Larch: A Forest History of Russia and its Empires (William Collins Jan 2026, £25) isn’t quite out. This new book by an American cultural historian looks really great. It also does several important things. It reminds us that Russia is more than just psychopathic tyrants and corrupt billionaires. It holds more trees than there are stars in our galaxy; it is home to some amazing indigenous peoples, such as the Khanty, who believe in silence as a gesture of respect to the forest and its inhabitants, who had no concept of Nature or wilderness and who recognised no division between the forest and home. These are my kind of people, my sort of place. Pinkham’s book promises to be important. I am reviewing it shortly.

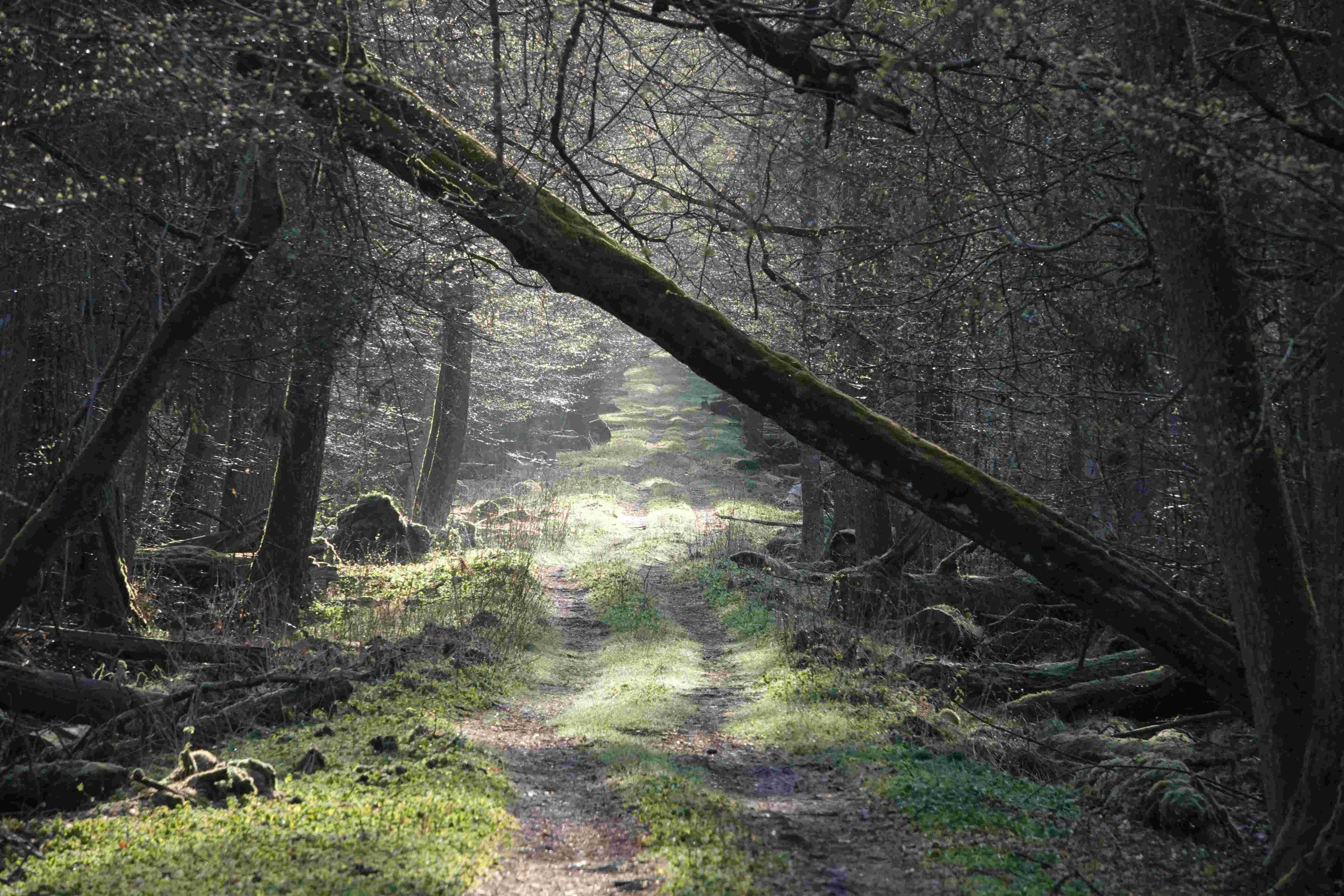

Finally did you know that Boris Yeltsin with the leaders of Ukraine and Belorussia signed the dissolution of the USSR in Belovezha? This is the Belorus side of the greatest forest in Europe known as Bialowieza, in Poland. I saw it briefly in April. My wildlife encounter of the year: so, here’s an image interlude on this extraordinary place. The main takeaway for Britons from Bialowieza, is our unwillingness to acknowledge that, in woods, death and life are one. Dead wood is new life. More life. Tidiness, by contrast, is lifelessness.

The tree theme continues because all those books sent me back to Peter Thomas’s Trees, HarperCollins, 512pp, 2022,

It is quite simply the best New Naturalist I’ve ever read. You can pick it up secondhand as a bargain for c£20. It is indispensible for anyone who cares deeply about Nature, woods and life. In a way it is as mind-stretching as Powers’ The Overstory

Paul Redshaw has self-published this lovely object: The Dales Slipper: Past – Present: A Revealing Investigative Account, pbk, 270pp, £19.99 It is a meticulous trawl and exploration of arguably the most charismatic flowering plant in Britain, the lady’s slipper orchid. The creature is known from just a handful of sites in northern England. I am hoping to go with Paul in 2026 to fulfil a lifetime’s ambition. You can buy the book or speak to Paul thedalesslipper@gmail.com.

Paul’s superb book led me back to Peter Marren’s glorious Rare Plants, British Wildlife, 2024, 396pp, £28. Like all Peter’s book it is worth reading for his lifetime’s accumulation of expertise. In this instance it is doubly rich because he has had two goes at the same title. A rare feat indeed by a rare scholar of Nature.

One of my book highlights in 2025 was Carl Safina’s Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, Souvenir, 2016, £9.99. Grounded in extensive field observation as well as scrutiny of the latest scientific literature, Beyond Words dismantles the age-old presumptions that every invidual animal – wolf, orca, elepant or chimpanzee – is nothing more than a representative of a generic organism; worse, that each animal has no individual agency, no feeling, no cognitive capability above instinct and no deep-rooted connection to its fellows. Safina thoughtfully but firmly obliterates the old Cartesian myth that we are the only species with consciousness and emotions. It set me thinking, in the context of my own discovery of the year. In 2025 I investigated the mimicry performed by singing male common redstarts. So far I have identified the vocalisations of 60 other bird species in the songs of male common redstarts. Safina’s book unleashed a world of speculation about what is happening and why each bird would do this and how it does it?

Probably the closest I will ever get to the Arctic is reading this frozen-white-knuckle ride of a thriller by Harry Whitehead, Claret Press 267 pp, pbk £11.95. White Road is both a page-turning disaster drama and a moral re-examination of the climate crisis and our species’ relentless need for more hydrocarbons. The author attends to the hour-by-hour twists in his plot, yet spliced to a forensic exploration of the human heart. He gives us a love letter to the extraordinary ice world of the Arctic: both its fragile beauty and its remorseless terrors. Before everything, the book strikes me as a singular, beautifully integrated achievement.

Health warning: if hard truths are not your thing, go no further. Earth Capital: The Long History of Capitalism and Its Aftermath: Alessandro Stanziani, Polity, 360p, £25, is not an easy read, but it is, as Thomas Piketty writes, ‘a must read’. Stanziani follows a singularly troubling inquiry into the way capitalism has interacted and shaped both us and the biosphere. Most powerful of all are the book’s revelations about the way largely Western capitalist entities are strengthening their grip on planetary resources. What possible hope for justice and equity can we hold when ten multinational corporations possess more wealth than the poorest 180 countries on Earth?

Just Earth: How a Fairer World Will Save the Planet, Tony Juniper, Bloomsbury, £20, 350pp. In his most important book so far, the chair of Natural England demolishes the arguments, often advanced by the super-rich to defend their interests, that Nature is an expensive luxury and its despoilation are the inevitable consequences of wealth creation. Juniper marshals his evidence brilliantly and shows how social justice and living within the means of our planet are part of a single achievable political project.

Finally the brilliant Jay Griffiths explores and amplifies some of the ideas discussed in Safina’s Beyond Words. Griffith’s own How Animals Heal Us, Hamish Hamilton, £20, is superb on these themes and especially in making a case for living with animals. I am so delighted that Jay is coming here (to Derbyshire) to talk about her new book in the Buxton International Festival. i hope you will join us in leafy July.

A Singular Triumph.

Richard Fortey, A Curious Boy, William Collins, £20, 2021.

This is not so much a review, as a way to commemorate Richard Fortey. Yesterday we received the immensely sad news that he has died aged 79. For those who didn’t know him or his work, then perhaps read on. Suffice to add that he was a truly lovely human being, brilliant, funny and immensely modest.

It is a frequent fun exercise among naturalists to try to pinpoint a childhood moment when they deviated from the path of ‘ordinary’ people and set out on their tangent towards the other parts of life. American birders use a nice shorthand expression for such an epiphany – ‘the spark bird’ – the encounter that switched on the nature-loving light.

This wonderfully lyrical autobiography is constructed around a search for an answer to that question. And it is important because ultimately it has shaped Richard Fortey’s whole life. At the end of the memoir we see him become one of Britain’s top palaeontologists, a world expert on trilobites, a celebrated author on the earth sciences and a television presenter of wildlife programmes.

Yet the heights he achieved in later years were not clear at the outset. Being in thrall to nature in the 1950s was hardly a choice with many career prospects. Most naturalists admit to an early anxiety about fitting in, especially at school where ridicule of the ‘nature nerd’ was a common form of torture. Fortey the public man goes back to reunite himself with his awkward, bashful, intensely clever youthful self to see if he can spot the moment of transformation.

He defines his family as ‘middle middle class’, and describes a postwar childhood partly set in London, where his father ran several fishing shops, and partly at Boxford in Berkshire, where the Forteys had a country cottage. The latter was strategically close to the River Lambourne so that Fortey senior could indulge a passion for fly-fishing.

The author may go on to propose that ‘I was first made on a riverbank’ but it turns out not to be a simple matter of family tradition and paternal genes. While the father was a record-setting angler, a scratch golfer and school champion at boxing and fives, the son was an outdoors disaster. The closest he seems to have come to any sporting prowess was a semi-serious ability at tiddlywinks.

What his family fishing excursions did provide, however, was a free-form space in which Fortey could find his own paths. And what an instructive set of enthusiasms they turned out to be. He takes us along on his bird-nest robbing excursions which, while full of a sense of visceral and life defining adventure, were also totally illegal by 1954. Taking birds eggs may be completely frowned upon by today’s environmentalists but almost every naturalist of this vintage admits to the same forbidden heritage. Me included.

Fossil hunting was a slightly more esoteric pastime but what is perhaps most telling about Fortey’s childhood was his awakening to toadstools. Today there is a whole library of richly illustrated guides and scholarly works on mushrooms. The fungus foray is a hugely popular activity offered for public participation up and down the country. Yet when Fortey did it there were no teachers and the only widely available book was the Observer’s Book of Common Fungi. It covered 200 of the many thousands of British species. Fungi, in short, are difficult.

The author tells us he remains an amateur enthusiast but it is a mark of his ability that he describes how in 2006 he found a tiny fungi Ceriporiopsis herbicola new to science. The discovery of entirely unknown organisms happens to few, but it happens in Britain to almost none. You realise that a challenge in this funny and entertaining book is peeling back the curtain of the author’s self-deprecation.

I would also suggest that the real revelation of A Curious Boy is something other than the way these multiple childhood stories converge at his contemporary self. I can illustrate it by invoking the author’s description of the Pembrokeshire landscapes where he went on family holidays. ‘The glory of St David’s is its coastline’ he writes, ‘nothing here remains horizontal and the rock beds are often twisted tortuously into folds, or abruptly terminated by great faults that cut vertically as if to ignore the geology altogether’.

Different colours were juxtaposed when the earth’s crust was sliced into these chunks: Caerfi Bay is backed by bright red shale; Solva displays black slaty rocks; massive, subtly coloured sandstones define promontories. Most implacable of all is St David’s Head.

This is an example of what his old schoolmaster called ‘Fortey’s forte’: his ability to see and interpret the complexities of the living world, as if from a great height, and then to compress all the technical material into a scientifically accurate form that is also full of poetry and music.

What we really learn from the autobiography is its author polymathic aspirations, his childhood passion for rather arcane composers – Constant Lambert, Maxwell Davies and Lennox Berkeley – for polyphonic music and choral singing. Another youthful trait was an omnivorous consumption of European literature (Beckett and Ionesco) , a taste for writing poetry that survived into adulthood, as well as a love of painting, which could easily have been his real metier. At A level he took both science and art.

Fortey writes midway through the text: ‘It took me much of my life to reintegrate myself into the person I was when I was sixteen.’ That’s the most compelling insight of the book: the way in which its author has striven to fuse and harmonise, often against career typecasting, professional constraint and simple circumstances, to become the whole person he wished to be. This is the substance of A Curious Boy and it strikes me that both the book and the life it recounts amount to a singular triumph.

Books really do furnish a Christmas

I get notice of, or receive, too many books to give due love to them all. As the holiday season approaches and we get to have leisure time for reading, I thought I’d post about some books you might want to mention to Santa. I haven’t read every one of them but, as my great late friend Tony Hare used to say, ‘I always judge a book by its cover’.

They are in no particular order:

- Ian Collins, Blythe Spirit: The Remarkable Life of Ronald Blythe, John Murrray £25, 404pp. The author, long-term friend and confidante of Ronald Blythe, has written the official biography. Affectionate, revelatory and wonderfully detailed, it describes the extraordinary life of the patron saint of English nature. It takes us from his impoverished country background (think of John Clare but in the 1930s) to his emergence as a key literary figure of 20th-century England. Blythe became friend to and collaborator with, or colleague of John, Christine and Paul Nash, Benjamin Britten, E M Forster, Richard Mabey, Julia Blackburn, Patricia Highsmith among many others. For those in Suffolk and Derbyshire I am interviewing Ian about the book on 1 June 2025 at Shimpling Park Farm and when he comes to the Buxton Festival on 24 July 2025. Dates for the diary!

2. Julian Hoffman, Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece, Elliott & Thompson, £18.99, 298 pp. It comes out in May 2025 and promises to be one of the nature books of the year, judging from Julian’s last book Irreplaceable. He writes exceptionally well and has plumbed his theme for half a lifetime. He introduced Maria and me to his adopted homeland – around the Prespa lakes, where Greece meets Northern Macedonia and Albania. His love and depth of knowledge of the region transformed it into one of our favourite Mediterranean places. I couldn’t recommend his work more highly.

3. David Perkins Hairy-foot, Long-tongue: Solitary Bees, biodiversity, evolution in your backyard, Whittles Publishing, £18, 187pp. The author’s ability to capture extraordinary forensic detail about the bees he has observed in the field or down his microscope is truly astonishing. The resulting drawings and paintings are worthy of Leonardo. To see and to be able copy what you see is at the heart of Perkins’ achievement. I reviewed the book for Country Life and wrote: ‘[It] is easily the best primer on the [bee] family that I have encountered.’ I love bees all the more because of it.

4. Jenny MacPherson, Stoats, Weasels, Martens and Polecats, Collins, £65, 372pp. The New Naturalist series, in which this is volume 149, has hit new highs in terms of quality. This looks a humdinger. I recently reviewed two of the series released earlier in 2024, which you can read here. MacPherson has brought the rapidly moving story – given the massive spread of pine martens in Scotland and now releases in Cumbria and elsewhere – bang up to date, while covering all the latest research on the group.

5. Princeton University Press recently started a ‘Little Book Of …’ series. Here are four – Fungi, Whales, Weather and Dinosaurs (NB there are also butterflies, beetles, spiders and trees). £12.99 a pop. Those of you of sufficient vintage can imagine the Observers’ series to get a sense of size and length (c150 pp). However the content is very different. Rather than offering, as the Observers’ did, a rather inadequate one-page-a-species account of about 100 organisms, Princeton give you a digested account of the whole subject. Written by experts but couched in highly accessible terms, they promise to be a great way of introducing yourself to new subjects. And they could be perfect for children.

6. Francois Sarano, In The Name of Sharks, Polity, £15.95 260pp, Sarrano is a former expedition leader on Cousteau’s research ship Calypso and has a lifetime’s experience of diving and firsthand encounters with sharks. He takes us through the science but also offers us a deeply felt personal defence of some of the world’s most remarkable animals. After reading this transformative book you might not want to get back in the water, but not because of the Spielberg-like nightmare, but because you will conclude that our world, with its seas and coastal shore – belongs to more than just the surfboard and jet-ski.

7. Richard Fortey, Close Encounters of the Fungal Kind: In Pursuit of Remarkable Mushrooms,, William Collins, £25, 328 pp. Fortey is best known as a paleonotologist and also as the unofficial biographer of all life on Earth. But the author began his journey towards Nature as a teenage mycologist. He explores this first love and trawls the weirdness of funga, as well as their place at the heart of all terrestrial life, while also debunking some of the more popular ‘ideas/myths’ that now engulf our understanding of myccorhizal relationships between flora and funga. Full of poetry, full of the extraordinariness of life, full of the author’s sense of wonder at it all – it is vintage Fortey (what his old headmaster called ‘Fortey’s forte!’) And please note that Richard’s book is propped up against one of his friends in our garden, hairy curtain crust!

8. If you need meat a little stronger for Xmas than veggie roast, here is historian Phillipp Blom’s Subjugate the Earth: The Beginning and End of Human Mastery over Nature, Polity Nov 2024, £25, 286 pp. Blom takes us through the materialist attitudes and philosophies, culminating in global capitalism, that have made of the whole living planet nothing but an instrument for our purposes. This a customary pro-Nature text with this key difference. He argues that the whole structure of our society is implicated. It is a great single-volume introduction to the biggest issues of our time.

Shieldbugs & Ponds, Pools and Puddles: UNOFFICIAL BOOKCLUB NO 12

Shieldbugs by Richard Jones, New Naturalist 147, Collins, £65, pbk £35

Ponds, Pools and Puddles Jeremy Biggs and Penny Williams, New Naturalist 148,, Collins, £65, pbk £35.

This is a long overdue piece on the last two in the New Naturalist series, which is, of course, not at all new. The full library dates back 80 years to a first title Butterflies by E B Ford in 1945. The postwar period was marked by a profound national upwelling of attention for the nonhuman world and the series was intended to capture and reinforce our new-found passions for nature. It’s hard for such a venerable list to sustain relevance and cutting-edge approaches but, if anything, the New Nats series has undergone a renaissance recently in quality and subject matter. Trees by Peter Thomas has the makings of a classic. And these two new titles match that high benchmark.

One thing that is striking is the trouble taken by the authors. It is particularly true of Ponds, Pools and Puddles, given that the volume was conceived even down to its title in the 1940s by the late Alistair Hardy. Biggs and Williams have picked up that baton thrown down long ago, but have taken a further 15 years to produce the book. That prolonged gestation is reflected in its exhaustive treatment of the theme – a whopping 611 pages – but the authors has also gained a huge advantage. There has been a revolution in understanding of, and depth of attention, for ponds, pools and puddles. The authors have captured all this new material. It means their book will be an important standard and key resource for a very long time.

At 450 pages, Shieldbugs by Richard Jones provides equally comprehensive coverage. I doubt the layperson would want material on this relatively small insect group that isn’t included here. Shieldbugs are in the order Hemiptera and comprise a cluster of families known as the Pentatomomorpha, of which there are nearly 18,000 species named worldwide and 190 in the UK. What is striking about them is their beauty. Their wings are protected underneath a harder sheath of chitin called a scutellum. These ‘shields’ are often astonishingly bright and colour-coordinated and the book is packed with beautiful images as Jones outlines his species-by species accounts and unpacks their identification.

The author’s own daughter, Verity Ure-Jones is also a talented artist and has done a wonderful job of capturing precisely the details of these remarkable insects. But more broadly one can see that the insects themselves are an artist’s dream and I briefly mention a beautiful book Heteroptera: The Beautiful and the Other, Scalo, 1998, by Swiss artist Cornelia Hesse-Honneger that Jones seems not to have known, despite his exhaustive trawl of the cultural resonances inspired by shieldbugs and despite CHH exhibiting at the brilliant Groundwork Gallery in Kings Lynn in 2020. Heteroptera excels in capturing shieldbug aesthetics.

While these little beasts possess what look like the elytra of beetles (the domed cases enclosing and protecting their wings), they are a very different type of insect. Beetles, like moths, or bees and wasps, proceed to adulthood via the total transformation known as metamorphosis. Shieldbugs do things differently, developing through a sequence of related stages or instars. The eggs turn into a little bug – technically a nymph – that progresses and shed its skin intermittently to acquire full adult condition. It is known as hemimetaboly and Jones gives a clear synoptic overview of the life-path for hemimetabolous insects and the underpinning biochemistry. He has a total grasp of the science while deploying prose that is fluent, engaging and precise. Here’s a small sample:

“When it is ready to hatch, the shieldbug embryo .. starts to swallow air and uses its inflating gut as a tough taut internal bladder against which it can increase the pressure of its haemolymph [insect blood]. Using rhythmic muscular movements it starts to expand its body, pushing the hard egg-burster up against the top of the eggshell. The shell bursts .. and the lid flips open. Empty eggshells usually have the hinged lids still attached and look like a stack of empty tin cans.”

The author is an arch proselytiser for his shieldbug religion and never misses opportunities to stray off-piste to capture amusing stories. I particularly love his account of the shieldbug pioneer George Kirkaldy. These details form part of Jones’ wider and superb historical account of all shieldbug research. But Kirkaldy (above: note how his moustache bespeaks mischief and salacity!) described a suite of new genera, which he named with the suffix -chisme. The word derives from the Greek for shieldbug Cimex. Undetected by his straightlaced entomological colleagues, cheeky old George honoured a suite of female friends with new shieldbug names such as Peggichisme, Florichisme. The pronunciation of these ends up as ‘Peggy-kiss-me’ and ‘Flori-kiss-me’. One assumes that Jones delights in this sort of thing partly to soften his subject and give it what we might call … ‘sex appeal’. It works brilliantly.

But on the issue of names I have to take to task, not so much Richard Jones, but the editors of the New Naturalists. This volume follows a pattern used in the series to cite English names for an animal or plant etc, on first mention and thereafter to use only scientific nomenclature. So, for example, the green shieldbug after a first encounter, becomes ever after Palomena prasina. Actually that is one of the slightly more memorable constructions: try to get your head round Gonocerus acuteangulatus (English name: box bug), or to take another group of insects, Pseudomogoplistes vicentae (the mole cricket).

The real problems arise when in a later chapter – say 30 pages after that first helpful inclusion of the English and Latin equivalents – you re-encounter the organism but only in its latinate form. You can’t remember who that name refers to and so you have to look it up in the index. By the time you’ve done that, you have lost the flow of the account and then you might have to repeat the same procedure – because the author refers to four other species only by scientific names – time after time after time. You could take the trouble to write them all out in your own private list, or you could annotate your own copy of the book every time you come across unfamiliar scientific nomenclature. But then why didn’t the authors and editors take on this task on your behalf? Why didn’t they implicitly set out to include you and me as readers of the book?

Names matter. They go to the heart of the whole naturalists’ project. And they go to the heart of the New Naturalists series. Who are the books for and what roles should they play? These are important matters and I think the Collins and New Naturalist editors are failing readers, but much more important, failing nature itself.

We are in the midst of the Sixth Extinction. One way of reversing the catastrophic loss of nature is to create stories that the public can understand and which help people to recognise the importance of the nonhuman living world. Richard Jones loves shieldbugs. He wants us also to love and care for them. He gives us stories that make them relevant. In fact, why else would you deploy a hugely accessible, humour-laced, easy-to-read style full of fascinating anecdote if that were not the purpose? Yet, when it comes to the name, the singlemost important and foundational part of the story-creating process, you have shut me out. And you are shutting out all those who, like me, love shieldbugs, but also love grasshoppers, dragonflies, butterflies, moths, bees, birds, mammals, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, plants, mosses and fungi. Like many others I conduct all my studies of these in English names.

Let’s clear away one matter. Scientific nomenclature is important and essential. I am not suggesting that it can only be with English names. In the case of Jeremy Biggs and Penny Williams’ glorious volume on ponds there are no common names for many of the aquatic organisms they are talking about. In fact, they break with the New Naturalist traditional format and seem to use a sensible and pragmatic mix of standard English wherever they can – frogs, newts, toads etc – with scientific nomneclature where there is no alternative.

One possible solution is for the editors at the New Nats to request common and scientific names in tandem. But what is particularly sad and important is that the New Naturalist series has now included major volumes on grasshoppers, solitary bees and bumblebees. Of grasshoppers we have just over 40 species in Britain. Of bumblebees there are fewer than 25. All of them have long-established, stable, widely used, and easy-to-remember common English names, but the authors of those volumes have insisted on using primarily confusing, difficult-to-remember scientific names such as Pseudomogoplistes vicentae.

To return finally to those wonderful shieldbugs: you tell me which is easier to acquire? which name allows you to start to create and understand stories about these fabulous organisms? A name like Gonocerus acuteangulatus or box bug? I rest my case.

The Complete Insect: UNOFFICIAL BOOKCLUB NO 11

The Complete Insect: Anatomy, Physiology, Evolution and Ecology, David Grimaldi (ed), Princeton University Press, £30.

If humanity is to shift up a gear in creating a sustainable civilisation, and thereby increase its own chances of survival, while safeguarding the rest of life on our extraordinary planet we need to improve relations with one specific group of organisms.

These creatures may contain in excess of 3.5 million different varieties. They play fundamental roles in clearing up much of the planet’s refuse and debris. They nourish many if not most of the worlds’ reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals. Actually, through plant pollination they make possible every third mouthful that humans take from a fork. These are just a few elements of their biosphere-creating relationships with the other key drivers of life – the 300,000+ species of flowering plant (called ‘angiosperms’).

We are, of course, talking about insects. While they are not alone in importance, they exemplify the unrecognised, largely unloved base of life’s pyramid. Without them we’re screwed. It is hard, therefore, not to be impressed with Princeton University Press’s drive to make popular this under-appreciated and often unloved group. Their recent series of family-based spotlight hardbacks on the big insect groups – beetles, ants, bees and now wasps – is overall a hugely valuable piece of advocacy and visual innovation.

Moths and flies are important pollinators as well as being astonishingly beautiful.

The latest, Wasps of the World by Simon van Noort and Gavin Broad, is for me a slight drop in standard, not in terms of the images or production, which are wonderful. The text is rather unimaginative and in keeping with the subtitle A Guide to Every Family, reads as a spreadsheet-like list of the numerical diversity present in various wasp genera and families. Surely, all those parasitoids wasp, with their ghoulish lifestyles straight out of Ridley Scott’s Alien should have supplied a richer assembly of stories to pique the public’s enthusiasm.

No matter. At the end of last year Princeton brought out what I judge the best in this suite of titles – a multi-authored work edited by AMNH curator David Grimaldi and simply called The Complete Insect. It is a brilliant single-volume synthesis of the whole extraordinary group, notable for its plain speaking and informational clarity. The graphics are exceptionally good.

The photographs here are as good as those in Princeton’s single-family monographs. See this exoskeleton of a beetle (above) for example

Being an enthusiastic amateur on insects, I need a very good overview and have had Blackwell’s The Insects: An Outline of Entomology by P J Gullan and P S Cranston since 2005. The new Princeton title, however, is an advance in terms of sumptuous imagery and heightened clarity. As the foreword announces ‘On the one hand it melds molecular- and chemical-level insights into anatomy, physiology and evolution’, while incorporat[ing] recent advances on microscopy and macrophotography to illustrate the incredible beauty of insects’.

Truly it achieves both. Insects are important because they require that we adjust the way we see the world. We have to look at them often with some kind of visual aid – a handlens or microscope. This refocusing makes us realise that most of life is not within the typical range of human vision. I think it is this decentring of our primary sense experience that makes the study of insect so morally important. It strikes me as no coincidence that two of the most important thinkers on the natural world – E O Wilson and Charles Darwin– looked at little things. We all need somehow to see how the world works in ways we seldom observe. Some of the representations of minutiae in this book truly take seeing and understanding to whole new levels. One example is this remarkable image of the underside of a tarsus (in effect, the sole of the foot) on a type of predatory diving beetle. The suction pads are made of tiny little filamentous hairs (setae) that enable the male to hold on to the female as they are mating. Sex has seldom seemed so psychedelic … man. This is a great book: I strongly recommend it.

Bohemian Waxwing: Europe’s bird-of-paradise

My winter has been crowned by a visitation of waxwings to Derbyshire that includes a congregation on the Monsal Trail near Bakewell of c360 birds, among the largest flocks ever recorded in the county. I have waited half a century to see even a group involving three figures but the sight and experience of these hundreds is nothing short of wondrous.

They possibly originate in northern Fenno-Scandia where they breed, but they could easily come from further east since waxwings encircle the Earth through the taiga forests of northern Russia and North America, reaching their western European limits in Finland or Sweden beyond the sixty-degree meridian. A striking aspect of waxwing appearances in Britain is that they are triggered by increases in the northern population possibly because of warmer, more productive conditions during their breeding season. The resulting over-abundance of fruit-eaters places pressure on local fruit supplies, which form the whole of the waxwings’ winter diet. For they are truly frugivores deluxe, more exclusively dependent on this food source than any other species. (Remarkably, while nesting, parent waxwings flycatch for insects and especially mosquitoes; so when next someone moans what use are mosquitoes: tell them they give rise to our winter’s most beautiful bird.)

If it is not the continent’s most dazzling songbird, it is in an elite cadre with wallcreeper and golden oriole and perhaps 1-2 others. Just look at the details that make up waxwing aesthetics. The bird’s whole plumage is dense and lax almost like luxuriant fur and then there is that black bandit’s mask, which can give its owner an occasional threatening shrike-like quality, although the way it sweeps up and back from the eye, which is itself framed delicately in white, reminds me of the kind of kohl-line beloved of Egyptian queens.

Then there is a double white stripe through the closed wing. The second, longer, outer ‘white’ line is actually not monochrome, but includes a lovely lemon yellow along the outer edges and tips of several main flight feathers. The secondaries are edged white but also tipped with outer ‘nibs’ of what looks to be red sealing wax (hence the name). Then, for good measure, the tail end is dipped in saffron-coloured ink. Even now I have left out the crowning glories of waxwing beauty: that shocking Madam Pompadour headcrest and those elongated undertail coverts which are the most exquisite shade of chestnut maroon. I’ve discovered that the best way to try to get to grips with all this feather-by-feather complexity is to try to draw or paint it. Trust me; it is … difficult. Here is the whole remarkable garb delineated on three berry-feeding birds.

Another joy of waxwings is their quest for fruit, which entails a miracle of navigation and relies upon the kind of aerial reconaissance of the landscape which our military planners could only dream about. Waxwings are dependent upon the rowan crop in northern latitudes but further south they are obliged to take other fare. At Hassop in Derbyshire it is the super-abundance of late hawthorn berries that has brought such numbers to one place.

By chance I happened to capture this individual above, technically LYW with colour rings on both legs (the title draws on Light [green], Yellow and White descending the left leg). It turns out to have been pre-trapped by a remarkable team including Raymond Duncan and the actual ringers Ally and Kev, who caught the birds in New Elgin, northern Scotland (512 km away) in one intensely successful operation on 13 November 2023. Remarkably, a friend Andy Gregory had captured images at Hassop of another coloured-ringed bird that had come out Ally and Kev’s bag three waxwings before my own LYW.

The two birds, both young males, had reunited in Derbyshire and could have travelled through half of Britain together. However, as Raymond tells me, the species shows little in-flock fidelity and Andy’s bird has now been sighted in Liverpool. Just to give you a sense of what puts the Bohemia in the bird’s official name, the New Elgin birds have now been sighted in the following places “Aberdeen 3/12, Dundee 20/11, Motherwell 28/11 and Ayr 11/12 and in England 2 in Lancashire in Barnoldswick 30/11 and Gainsborough 17/12; others in Carlisle 25/11; Newcastle 6/12; Whitley Bay N.Tyneside 11/12; Ipswich 13/12 and 17/12; 2 in Durham 23/12, 24/12 one of which had moved 145km NNW from Lincolnshire; Bakewell, Derbyshire; Brighouse W.Yorkshire and Langeland in Denmark”. (See the website of this fabulous Grampian Ringing Group here.) Some of their birds are now in Sussex 630 km from Elgin. Many are first-year juveniles and have never migrated before, yet they navigate our landscapes and find suitable food sources often entirely alone and ustilising only their innate resources.

Waxwings have been visiting the the middle latitudes of Europe and recognised by its citizens since the sixteenth century. The unpredictable nature of these sudden irruptions was treated with high suspicion by our ancestors and the waxwing was judged a bird of ill omen, fortelling imminent disaster. Even now in Holland they are called pest vogel, which roughly translates as ‘pestilence bird’. The appearance of waxwings in Europe in 1913/4 was taken as a sign of the First World War. Retrospectively, of course!

Truly, however, nothing could be further from the facts. Waxwings speak in complex ways of the wonderful interdependence of our world, both in terms of its geography and biology. For the birds not only eat berries and fruit, they also plant fruit-bearing trees. Some individuals have been recorded to consume three times their weight in berries a day and then, of course, sow the seeds of new life once they fertilise the wintering areas with waxwing poop. In keeping with the bird’s delicate aura, even its droppings are said at times to resemble string of pearls.

Trees, produce fruit precisely so that their reproduction and propagation can be completed by birds and no other European species is so devoted to that mutually beneficial exchange than the waxwing. However, another extraordinary avian family, mainly from New Guinea, that expresses this interdependence is the birds-of-paradise. Much of their incredible ecology not to mention their world-famous beauty draws from this mutualism.

Given that many of the waxwing’s favourite foods are produced by members of the family Rosaceae – rowan and sorbus berries, hawthorn and rosehip – the species is, in effect, a rose-gardener. it is fascinating to contemplate that the very word ‘paradise’ has its origins in ancient Persia (Old Persian pairidaeza, modern Farsi firdaus) almost 5000 years ago and was used to describe a tradition of enclosed arbors perfumed with the scent of the cultivated rose. Perhaps it is time to recognise that that this mysterious wanderer from the far north – the Bohemian waxwing – is in more ways than one Europe’s very own bird-of-paradise.

Volunteers ’23

In 2022 I remember how a major wildlife charity published with great fanfare a list of its favourite celebrities. Celebrities? I was …. unimpressed. With very few, notable exceptions, celebrities are to action-for-nature what bush tucker (off that god-awful tv programme) is to nature-connectedness. In short, the absolute inverse of what’s truly important. Much of the amazing work for nature is done by people who never ask for thanks, or attention, or even money. They are amateurs in its original (not in its derived) sense of lovers! They simply love wildlife. I’ve taken it upon myself to pay a little attention and offer small thanks to some of the remarkable people I’ve noticed or met in the last 12 months. Here are my choices.

First up: Colin Slator (right and behatted) with his long-time pal Stephen Worwood. The pic that Colin is holding (they are the middle two, looking suspicious) is from 40 years ago. Just before that period, Colin, aged 21, walked up to the door of the owners of High Batts, an area of riverine woodland on the banks of the Ure near Ripon. He asked them if he could rent it to look after the place for wildlife. A half century later there is a large network of local volunteers doing great stuff for wildlife at High Batts – events, recording, habitat improvement etc etc. The whole community is an exemplary expression of the Big Society. Many of them, Colin and Stephen included, are still doing it. It is, by anyone’s standards, an amazing achievement. I would suggest that it is more typical of how nature is being protected and valued in Britain. I wrote a little more about High Batts in the Guardian here.

Next comes Jonathan Mortin, whom i have known from school days, when we were aged about five. Jonny is one of those remarkable all-round naturalists, who has a special affinity with neglected taxa that hide under rocks or beneath bark. He cherishes what most people ignore or even despise. But he also loves and celebrates insects, plants, arachnids, crustacea, fungi. Most of these he identifies and enters on official website systems (iNaturalist, iRecord) that help to map where UK wildlife is living. Here in Britain we may be more nature depleted than almost all other countries on Earth, but my goodness we know where the last parts are located. It is an essential precondition of almost all meaningful nature action. To date he has logged c11.5k records of 2.8k species on iNaturalist alone. Let me tell you. That is one HELLUVALOT of dedicated recording. One important outcome locally is that he has drawn up an extraordinary map of biodiversity in our neighbourhood, almost singlehandedly (though he has a major partner-in-recording crime in the equally amazing Steve Orridge) involving 100s of hours of work, without any fanfare. It’s amazing. And if you are inspired to do likewise, then he helps run sessions where you can learn how to get to grips with iRecord and iNaturalist. I am now a devotee.

Ruth Tingay is pretty much the entire staff of Raptor Persecution UK as an organisation. Yet it is recognised and valued internationally. She runs a website in the same name, meticulously documenting and investigating and recording for posterity, in the clearest prose, how the shooting-and-killing people of Britain illegally destroy wildlife, but especially raptors. They also kill all sorts of other animals and plants, which are often branded as vermin, including some of our most charismatic animals. Ruth is precise, targetted, relentless. Her work is a marvel. She pretty much defines how one individual can make a huge, and even a national difference. Those who wish to arrest our uplands in a highly impoverished and depleted condition (driven-grouse moors) so they can go on killing for pleasure, really really don’t love her and have at times persecuted her. She has a fantastic back-up team including her good friend Chris Packham (above). As for a celebrity who does great stuff …..

My last great volunteers are a double act. Rachel and Dave Purchase have done really fantastic stuff, building on the work of others, to create for our town (Buxton, Derbyshire) a first rate wildlife group the Buxton Field Club. We are taking action in all sorts of way, partly because of their shared input. Our meetings not only inform and keep members abreast of new ideas and developments, but increasingly the club’s work is making a difference for nature in our area. Jonathan Mortin’s initiative above is amplified and structured by the wider work that Rachel and Dave do for the BFC. we’re also branching out into wider and wider collaboration with other great volunteer groups in our area. All in all, it is another great example of how individuals, working together, make a big difference.

These are my volunteers for 2023. I hope you’ll agree. What they do is not just free but priceless.

Beetles of the World: Unofficial Bookclub No 10

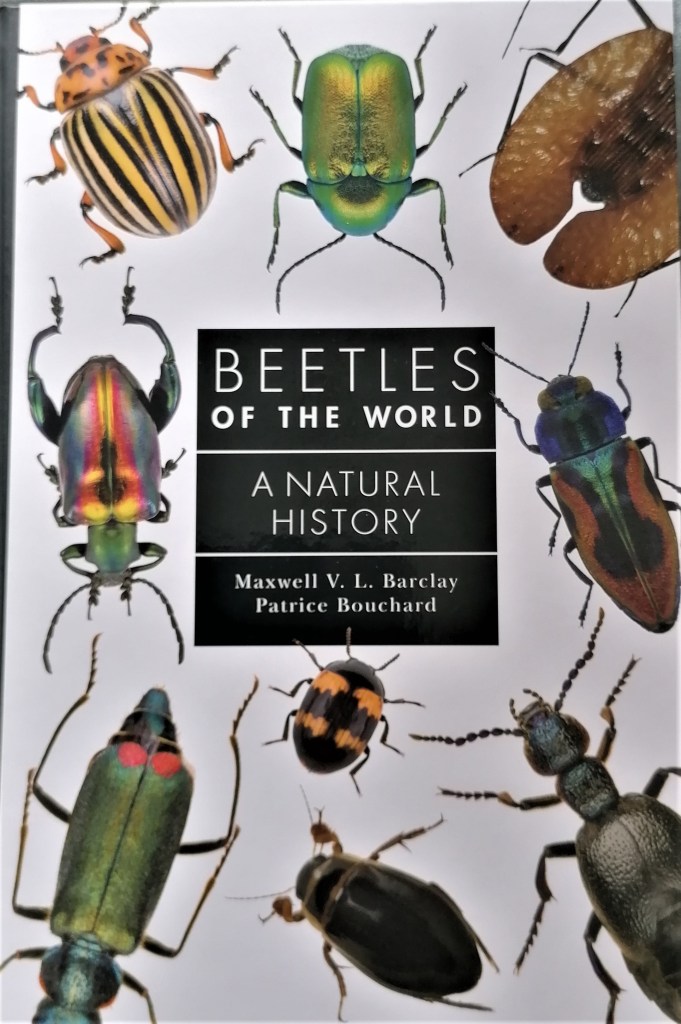

Beetles of the World: A Natural History, Maxwell V L Barclay & Patrice Bouchard, Princeton, hbk £25

It’s time to think of beetles as something other than a tiny black creature scuttling insignificantly through the vegetation. As Alfred Russell Wallace pointed out of the general public, ‘Tell them … they are ignorant of one of the most important groups of insects inhabiting the earth, and they think you are joking’. But no. Beetles are among the superpowers of terrestrial life. If humans vanished, there’d be barely a ripple in the biosphere’s functioning processes, except of course a massive, immediate upsurge in the abundance of almost everything else. Remove beetles from life and there would be major evolutionary ructions for hundreds of thousands, if not millions of years.

There is a lovely anecdote in this new book that trades on this near-incredible dominance of beetles. A famous biologist JBS Haldane was once approached by a group of Christians and asked whether his career had given him any insight into the mind of their deity. Back instantly came his response: She or He had ‘an inordinate fondness for beetles’. There are apparently 400,000 beetle species now named, representing by a massive margin the biggest order in the class Insecta. It equates to nearly a quarter of all life forms so far identified and they operate in a multitude of ways. They predate everything from whole trees to other beetles. They, in turn, are food for almost all life forms including bacteria and lions. They are pollinators deluxe for huge numbers of plants. Above all, they’re among the planet’s principal undertakers and refusal-disposal agents.

Now they star in this beautifully illustrated work from Princeton. The volume, in turn, forms part of the publisher’s charm offensive on behalf of the most overlooked, under-rated and downright despised of all animals – Insects! The entire series is evolving into a thing of beauty (not forgetting recent further titles on snakes, seaweeds and turtles). Yet at somewhere between £25 and £30 each, the question should be asked…. are they worth it?

I’m an author and biased, but to put the price in context, I recently heard of someone who bought a round of drinks at a London pub – two large glasses of wine and two pints of beer. For the price they paid for these four drinks (£112) you can get not just this beetle book, but the ants, the bees (see my review of that volume here) and a fabulous new survey called The Complete Insect: Anatomy, Physiology, Evolution and Ecology by David Grimaldi. The books will last you a whole lifetime: I rest my case.

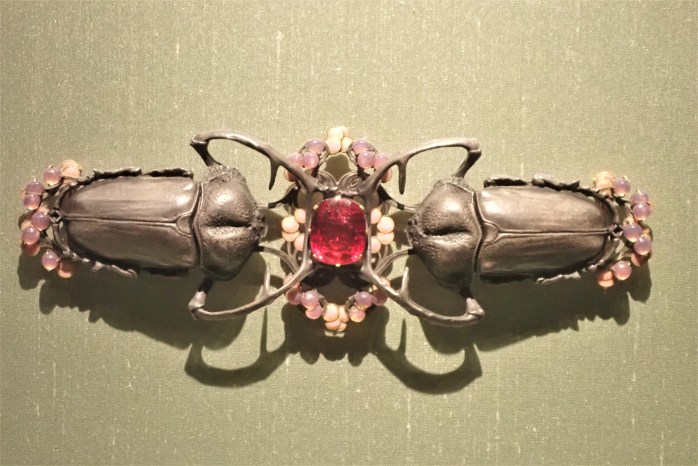

One takeaway highlighted by Barclay and Bouchard – aside the fact that beetles are eaten in many an Asian marketplace – is how beautiful the beasts can be. Look at this Filipino flower chafer above. There are 300 such images in their book. I’m not surprised that humans have been captivated by their extraordinary architectural structures as well as the shiny metallic colours of beetles. Look at these glorious stag beetles in a Lalique piece from the beginning of the twentieth century.

The book includes a section on this cultural importance to beetles – as inspiration for art and literature, but also as a source of ideas embedded in the religious beliefs of ancient Egyptians. Their god Khepri was evoked through images of scarab or dung beetles. The sight of these ubiquitous animals rolling their balls of dung across the ground was seen as symbol for the chief deity Ra, progressing the sun across the heavens. Somehow the ancient Egyptians intuited that there was some fundamental connection between the beetles’ reproductive habits, the passage of our daily star and the totality of life. And how right they were!

I want to add a further observation about the beauty created by beetles and also about their centrality to life.

Recently I found this series of patterned excavations inscribed on the surface of a dead tree by a member in the bark beetle family the Scolytidae. This species is a vector of so-called Dutch elm disease, which has removed most of the mature elms from the British landscape, decimating many millions of trees in the process.

The story involves a pathogenic fungus rather wonderfully named Ophiostoma (the snake-mouthed). It works in harmony with the bark beetle to spread fungus spores tree to tree. In return, the fungus detoxifies the elm’s defensive chemicals, it helps to break down tree tissue and prepare it as food fit for a small beetle. In addition, the two predators – beetle and fungus – create an effect that turns the elm upon itself. The fungus somehow encourages the tree to produce chemical signals that are attractive to yet more bark beetles. Elms are thus recruiting the agents of their own demise. It may not be beautiful in any conventional sense, but this much-lamented process entails its own kind of exquisite complexity. It also shows how we think of the British countryside as somehow belonging to us, and that is ours to do with as we wish. When it comes to wholesale landscape changes, however, beetles are easily as capable. Beetles are beautiful and brilliant and powerful. This superb book shows us exactly how.

Bee Aware: my Unofficial BOOKCLUB NO 9

Solitary Bees by Ted Benton and Nick Owens, New Naturalist Library, William Collins, £35 pbk.

The superb Field Guide to the Bees of Britain and Ireland by Steven Falk and Richard Lewington (2015) is probably my most constant companion after any wildlife excursion in summer. It has decisively placed bees on the radar for many naturalists. Yet if that book teaches us anything, it is how these insect comprise an enormously complex and difficult group to identify. As an illustration, the most diverse genus, the mining bees (Andrena), includes 67 species and many of them are remarkably similar in appearance. Of necessity, the field guide, covering c275 species, focuses almost entirely on how you tell one bee from another.

Yet many of the solitary bees have fascinating lifestyles. One I love is (above) the ivy bee Colletes hederae, which was only recorded for science in 1993, arrived in Britain in 2001 and has since spread as far north as Derbyshire, where I saw it last year. Perhaps the solitary bees that many know best – from the bee-sized capes they snip out your rose leaves – are the gorgeous leafcutters (Megachile). They use these vegetative borrowings to build little leaf-tubes in which they rear their young and are now regular breeders in garden ‘bee hotels’.

Unfortunately much of this extraordinary behaviour by solitary bees was hard to study except in the pages of specialist journals. Not any more! Here comes a whopping tome by two top UK entomologists that includes as much information as you could ever wish for. At 596 pages it is a veritable encyclopedia packed with detail. Like many of the latest New Naturalists it is also full of great photos, the majority by the authors and, if not truly a field guide, it will surely be a supplement for identification purposes. The pics are especially rich on social behaviour. I loved Nick Owen’s visual materials on the ways bees interact with possible competitors and his 60-page chapter Parasites and Predators is a highlight.

However, it is the overall richness of new information on the character, ecology and behaviour of solitary bees that is the chief virtue of the book. It divides into ten chapters including accounts of the diversity of solitary bees, of their sex lives and of their wider life cycles, but especially their nesting behaviours, as well as a chapter on their status and conservation. A further section covers how more evolved bees (bumblebees and honeybees) acquired their social livestyles from originally solitary species, but also how some social bees have reverted to solitary reproductive systems or, occasionally, exhibit both solitary and social tendencies. I found this the most challenging, with prose occasionally dense with technical terms that were hard to process. (eg ‘Phylogenies were reconstructed by a method involving electrical separation of the enzymes [allozymes] coded by alleles at selected loci in the genomes of bees belonging to species with known behavioural repertoires’.) It is not a book for casual bee observers and this part requires a high degree of pre-existing knowledge.

Not so the two longest chapters. At 130 pages between them – and almost a book within the book – the two-part summary of inter-relationships between flowers and bees is also the heart of the whole work. Three quarters of flowering plants require the neurological systems of animals to complete their reproduction. As many as one in ten animals worldwide play a role in plant sex, but it is the contributions made by the different groups that surprised me: moths and butterflies (140,000 species), beetles (77,000), bees, wasps, ants and relatives (70,000) and flies (55,000). While these figures indicate the range of pollinators, they don’t measure who is doing the really heavy lifting. Studies show that bees are make the biggest contribution of all.

The stats were fascinating. What I really love is the descriptions of the varied strategies, used by both plants and insects, to exploit one another. Many plants can self fertilise in extremis, but bees underpin the full genetic health of vegetation through their cross-pollination services. Plants do everything to maximise this outcome. Flower shape is one mechanism. Many pea family members, for instance, have flowers that restrict access to bees with the right length of tongue or with pollen brushes in the right places. Plants also flag their nectar wares with colour and line, or issue alluring scents to fool insects. Orchids even mimic the sex pheromones produced by female insects and trick male bees into pseudo-copulation.

Other species modulate nectar supply in the course of each day. Celandines open and close in line with daytime temperature. Others, including members of the daisy family, shut up shop by midday (to avoid being eaten by flower-eating animals). They then open again when it’s most propitious. Plants also stagger the appearance of male then the female parts of the flower to avoid self-pollination, and also encourage bees to move one flower to another to spread the pollen and their genes. Not all of it is honest work. For example, flowers that are not nectar-rich are thought to mimic the colours and appearance of plants which are. In this way they persuade bees to visit without incurring the high energy costs of nectar production.

A flower meadow looks complex. It is complex (I’ve written about it here. But more than that. You realise that every single insect and almost every bloom is making hour by hour, minute by minute, adjustments to maximise harvest, or conversely, to enhance reproductive success. It is a kind of chaos of individuals, all pursuing separate agendas, often competing, sometimes practising sneaky, cheating ways to achieve their private goals; yet all, ultimately contribute to the success of the whole.

Flowers and insects are truly part of the bedrock of life on Earth. Every third mouthful we eat is thought to originate in these relationships. If we are truly – as the saying goes – what we eat, then at some level we are insects and plants. This book helps you to see how and why. It also allows you to understand that solitary bees are at the heart of flower-rich ecosystems. After reading this painstaking study they’ve never seemed more interesting. Solitary Bees could only have been written by two authors each of whom has a lifetime of research to enrich their understanding.

Above are two of my favourite recent solitary bee sightings: Spined Mason Bee (left) which just reaches Derbyshire and makes its nest in old snail shells. But looks at the orbs of this Green-eyed Flower Bee, seen at Beachy Head!

UNOFFICIAL BOOKCLUB NO 8

Gerry Maguire Thompson Rewilding an Urban Garden: An Illustrated Diary of Nature’s Year, Wild Books, £9.99. A link to Gerry and Marina’s website is here

So often we hear about the crisis of climate change and the sixth extinction and feel not only overwhelmed by the scale of the problems, but also helpless to make a difference. For me, the main takeaway from this delightful book is that no action is too insignificant, no piece of ground too small for you to change the world. If you want to know how to go about rewilding your own domestic soul, it offers a multitude of hot tips while infecting you with its author’s own deep passion for the outcome.

We also have a wildlife friendly patch. Our sighting of the day is a worker bilberry bumblebee, my favourite among all its glorious family members.

Yet Thompson has attracted new neighbours to his plot that make me green with envy: stag beetles, wood mice, hedgehogs, holly blue butterflies and foxes. Over the course of the book, he supplies not just the practical know how; he also illuminates what fascination, health-giving mental absorption, entertainment and endless daily drama you acquire when you fill your own part of the Earth with homes fit for a 1000 other species.

There are two things I really love about this upbeat, do-it-yourself book. The Thompson couple – Gerry and Marina – have published the book but also filled it with delightful nature-rich illustrations. For the sheer diversity of creatures packed into every pic they remind me of the fabulous work of Charles Tunnicliffe for the Look series by Ladybird books. Here’s an example.

The other thing that stands out is that no creature is too commonplace to enjoy the attention of the author. For their busy-ness, infectious social lives and their overlooked background music, Thompson declares himself a ‘sparraholic’. Alas house sparrows have declined in Britain probably by well over 60%, but especially in urban areas. Not, however, in the Thompson nature reserve, which is exactly what their garden is. And if all of us did what the author’s family are doing, we could scale up from a few, to many, to all gardens. Then we would revitalise something like 2 million acres of very important habitat. As I said, no plot is too small for you to change the world.